Men: 100,000 Years of Uselessness

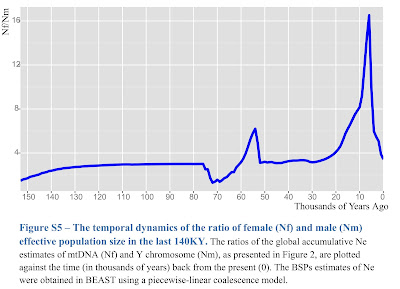

What's fascinating is that it appears male disposability has been the rule rather than the exception over a large part of our past. This paper created quite a stir in the world of population genetics three years ago. It tracked the effective population size (from the standpoint of reproduction) of men and woman over the last 150,000 years, by looking at divergence rates of Y chromosomes and mitochondrial DNA. And the pay dirt is this (supplemental) figure.

Women, on average, have had far greater reproductive success than men. Particularly fascinating was the spike in the last 10,000 years, which the authors and others have correlated with the transition from hunter-gatherer to pastoralist (by looking at the time sequence of its appearance in different parts of the world). At its height, 17 women were reproducing for every man; conversely, 95% of men were not reproducing at all. What sort of society led to a bizarre ratio like that is, at the moment, anyone's guess. But more generally, over the last 100,000 years, men were generally only about a third as likely to reproduce as women (the blip around 70,000 y.b.p. may be the Toba bottleneck.) According to these data, humans, historically, have rarely been monogamous; the pattern seems to be polygyny. The non-reproducing males might have had some role in the culture, but as far as reproduction is concern, they might as well never have existed.

So the spread of monogamy over the very recent historical past is an anomaly; a short era of male usefulness. It came at a price; for example, on my maternal line, my great grandmother Maggie O Neill's husband, who probably wasn't a great provider anyway (he was a carter in Northern Ireland, which meant he delivered goods using a hand-cart), but was spectacularly reproductively successful, died when he was 49, leaving her at 39 years old with ten children. She survived, even prospered; she bought a very nice house in the center of Belfast 13 years later. I have no idea how she managed that, things being the way they were in late 19th century Ireland, and my speculations have, let's say, been met with a degree of hostility from other members of my family. And great-grandfather Dan's utility was about to end anyway. Once we had delivery vans and trucks, carters went the way of buggy whips.

I wouldn't be the first, of course, to note the problems that society has when there are supernumerary men. And I submit many of the problems we have right now, problems that have slowly developed over the last quarter century or longer, are mostly a product of male uselessness and more importantly men's perception of their own uselessness. The drive to return to an era of restricted sex roles; the drive to control women's reproduction; the hostility to perceived threats, either internal (racial minorities) or external (aliens); all seem to be rooted in male insecurity, an insecurity, which by the way, is entirely well-founded, and may well have been bred into us all. 100,000 years is plenty of time for evolutionary change. But it's also manifest in more mundane, even pathetic ways. A man yesterday assured me he needed access to an unsecured gun in his home because he needs to be able to protect his family. Dude, I told him, you live in Lincoln Nebraska, do you seriously think your family is at risk from intruders? I've lived 40 years in America, some of the time in far more dangerous places, and I've never had a single instance where my family was at threat or I wished I had a gun to protect them. OK, it's a very small risk, he said, but it's a risk. I replied that just having the gun around is a bigger risk. But that's not the point, really. The gun gave him the illusion of being useful, even necessary.

So, yeah, at the moment, men are a problem. We're trying to shoehorn society back into the 1950s. We're being ever more emphatic about having a hold on the reins of society: witness the spectacle of 11 white men on the Senate Judiciary committee trying to force through the nomination of another white man expected to lock up that whole abortion thang.

I write this not out of some compulsion to self-flagellate. I have three kids, and am smugly satisfied with my own usefulness. I say it not out of a sense of collective guilt, (something of which I've recently been accused) It's not my fault these guys are staring into the abyss, and panicking. I take absolutely no responsibility for their angst, and in fact find it strangely amusing (yeah, I'm evil). I don't feel it necessary to proclaim #notallmen; of course, #notallmen, duh! I write it in recognition we have a problem; it's a problem primarily for men and only secondarily for women, but it's a big problem. And men could be really useful to society by doing something constructive to solve it.

I have my own ideas, of course, but let's start with the traditional step one.

Comments

Post a Comment