The Fortenberry slaves: a prelude

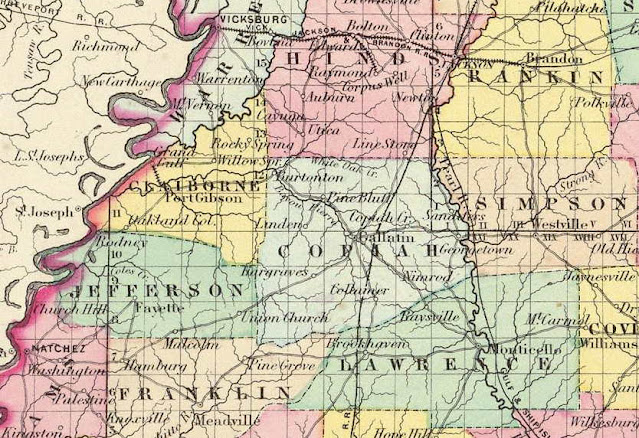

Toiling in the mid-morning sun, in a hot, muddy cotton field in Copiah County, in the south of Mississippi, three young African American men, brothers, aged 18, 20 and 22, hoed the rows. It was late June, 1860, and so the men were slaves. The ground was wet from yesterday’s rain, the air heavy, and the men were anxious to finish their work before the clouds gathering on the western horizon flooded the fields with another summer cloudburst.

Inside the plantation house, unbeknownst to them, they were being enumerated. James R Fortenberry, the slave-holder, a man of about 35, was listing their important personal details to Elijah Peyton, Assistant Marshall. These details were three; age, gender, and race. The race was officially ‘mulatto’; at that time, and in that place, mulattos were usually the sons or daughters of a black woman raped by a white slave-holder. They had no names, as far as the United States Government was concerned. Instead they would be listed, in Peyton’s elegant, almost foppish handwriting, under the name of the man who ‘owned’ them. They, and thousands of others, would be then be tallied; Copiah County Mississippi at the time had about 7000 free human beings and at least 8,000 slaves. How many slaves exactly is unclear; the Federal Schedule for the county runs to 100 pages, with 80 human beings (plus slave holders) per page, and it is full to the last line. One gets the feeling Mr Peyton simply ran out of space.

8000 slaves meant 4800 extra votes for Copiah County in the upcoming presidential election.

James R Fortenberry declared a personal worth of $10,500 in the 1860 census, a lot of money in those days. The slaves were purchased fairly recently; he owned only one, an older lady, in 1850. He loved his slaves so much he went to war to continue his right to have them. His military career was undistinguished, but afterwards he was able to return to Hazlehurst, Mississippi, and his real estate, though not his human property. Eventually he had seven white children.

One of his younger sons, William Madison Fortenberry, moved to Tangipahoa, Louisiana, and owned a farm and dry goods store. There were also African-American Fortenberrys in ‘Bloody” Tangipahoa Parish; the area had the one of the highest rate of lynchings in the post-reconstruction South. As late as 1999, it voted to send David Duke to Congress.

William’s son, Luther Sexton Fortenberry, graduated from segregated Tulane with a degree in medicine, and, a captain in the US Army Medical Corps, was killed by a landmine in France in 1944. His grandson Luther Sexton Fortenberry Jr., married, divorced, and died in a car accident.

His great-grandson became Congressman Jeff Fortenberry of Nebraska.

He’s cleaned up nicely.

Comments

Post a Comment