The Fortenberry saga, Chapter 1: James R. Fortenberry, slave-holder and reluctant warrior

For the prelude to this chapter, see here.

James R Fortenberry, 2nd great-grandfather of Congressman Jeff Fortenberry, was born in 1826 or thereabouts, in Copiah Co., Mississippi.

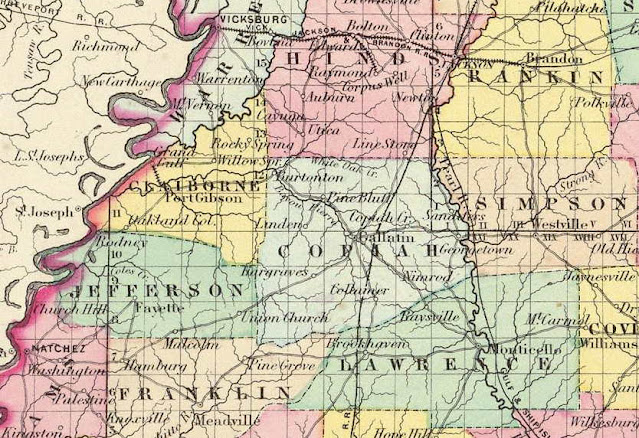

Copiah County Mississippi in the 1820s was the sticky southern edge of the American frontier, a bug-infested alligator-ridden swamp on the far edge of the new Republic. Whites had only recently stolen this particular swath of Native American land. The ‘treaty’ of Doak’s Stand secured what is now the western part of Mississippi for the whites. It was ceded to the United States after murderous thug and soon-to-be second-worst-president-ever Andrew Jackson threatened to destroy the Choctaw Nation if they refused to sign. The land became the huge Hind’s County is 1821; and was then broken up into manageable chunks in 1823, the southernmest corner becoming Copiah County. Copiah was the Choctaw word for calling panther. Wypipo for sentimental reasons liked to name newly settled land in the language of the people from whom they’d stolen it.

James R Fortenberry was born in Copiah County some time in the mid 1820s. Though not Presbyterians themselves, his parents, following God’s command, had marched forth from the Carolinas, as they burgeoned with Presbyterian fecundity, finding their way to the newly annexed territory. We know little of JR’s early life, untl at the age of 20 or so he married 15 years-and-3 months-old Mary Ann Wilson in 1846. This was, after all, Mississippi.

Missippians at the time frenetically bought and sold land, and they frenetically bought and sold and bred slaves — many many slaves — and grew cotton, and engaged in all manner of criminality — the level of violence was staggering. It would be more accurate, of course, to say the slaves grew cotton; the only tools whites brought to the fields were overseers’ whips. Slavery was made official public policy of the state in 1847., and from 1850-1860, it flirted with the idea of secession, being one of the first to secede in early 1861.

So JR, as he usually signed himself, expanded his household in Gallatin, the county seat, with children and slaves. Eugenia came in November 1847; then Mary (1852); Daniel Luther (1854); William Madison (1856); and Susan (1859), His mother, Mary Taylor Fortenberry lived next door in 1850. Evidently a widow, she re-married, at the age of 60, in 1854, to a Joseph Price Senior, but was back with JR and May Ann by 1860.

His slaveholdings grew apace. He had one slave, a 14 year old black boy, in 1850. By 1860 he held 4 mulatto males, aged 22, 20 18, and 6, and one black female, 26.

By 1860, there was a new railroad, from Jackson to New Orleans, with a stop in nearby Hazlehurst, which thereupon became the county seat, and JR moved there. He was worth $10,000 at the time, mostly in the value of his slaves. He rented the land they worked, from one of the few Choctaw who had declined to travel the Trail of Tears, and had remained, facing every-increasing racism.

Despite his by now considerable financial interest in the continuance of slavery, James R Fortenberry showed no great eagerness to fight in the Army of the Confederacy. In fact, his enlistment, in Company E of the 36th Mississippi Volunteers (Hazlehurst Fencibles), under Captain John Warren Ward, came more than a year after the beginning of the war, and was likely a result of the introduction of conscription in early 1862. So, in March 1862 JR took the railroad to Meridian Mississippi, a distance of 143 miles to the east, to enlist, and the regiment mustered out on April 1. It marched 200 miles north toward Corinth, on the far northern border of the state. Corinth lies about 90 miles east of Memphis, Tennessee, and was a major railroad center, where Beauregard had retreated after Grant defeated him at the battle of Shiloh.

Beauregard, the codesigner of the now-notorious Confederate Battle Standard, had been consigned to the western theater because of friction with the Army of Virginia. He was a cantankerous man and a mediocre general, who upon the arrival in Tennessee, bungled the organization of his forces at Shiloh, and was driven back into Mississippi with heavy casualties and his tail between his legs.

Meanwhile, the hapless 36th Mississippi, undrilled and untrained, arrived in Corinth just in time for one of the preliminary skirmishes of the siege of Corinth. Their first engagement at Farmington, on the city outskirts, on May 9, was a disaster. The regiment was described as ‘straggling to the rear’ apparently having heard a mysterious order to fall back. Eventually, ordered to charge, ‘a larger portion’ did so. One suspects Sergeant Fortenberry was not part of the ‘larger portion’. 6 days after the battle he was sent back to Hazlewood Hospital, and ignominiously reduced in rank from sergeant to private.

He remained in hospital for two years, unpaid and listed as absent from his regiment. It is probably not too harsh to suggest that Fortenberry’s primary ailment was an allergy to the smell of black powder. Reading between the lines of the Confederate dispatches, it appears the 36th Mississippi completely jeopardized Confederate efforts, and JR played an inglorious part in this.

And it was all in vain. Beauregard abandoned Corinth later in the month, ceding to the Union control of one of the major east-west railroad routes. He took his wounded and most of the heavy gear by train to Tupelo. Memphis fell soon afterwards, giving the Union control of most of the Mississippi river, and eventually enabling the seizure of Vicksburg.

Mississippi as a whole did not have a good war. After Grant captured Vicksburg and then Jackson, Sherman was allowed to march across the whole width of the state to Meridian and further, destroying the railroad and anything of possible military use, in a preview of his famous 'March to the Sea'. Grant was determined there would be no counterattack against the river. By late 1863, it was estimated that the vast majority of Mississippi's once-slaves were free. In fact, Mississippi had the distinction of contributing more men to the Union Army -- almost all of them black -- than to the Army of the Confederacy.

JR remained in the hospital through 1864. His time as an invalid was was not entirely unproductive. His daughter Sallie was born in 1864, and therefore conceived during his indisposition. Possibly he was not too terribly badly wounded. Or wounded at all.

Although the Union Army did not consider it worthwhile to take most of the interior of Mississippi, concentrating on controlling the river, they did launch one swashbuckling raid to disrupt Confederate communications. Colonel Benjamin Grierson’s cavalry brigade of 1700 Iowa and Illinois horse troopers drove 600 miles through enemy terirtory from Tennessee to Baton Rouge in May 1863, tearing up the railroad, ripping up bridges, burning storehouses, freeing slaves, and generally wreaking havoc. In the process they burned the rolling stock at Hazlehurst railroad station, and chivalrously helped the townspeople prevent the fire from spreading to other buildings. Fortenberry’s presence is not noted in any of the accounts of the raid. He was likely hidden under a bed.

In the fall of 1864, after a proclamation by Nathan Bedford Forrest, notorious founder of the KKK, Fortenberry was rousted out of his bed and dragooned into Powers’ regiment, which performed safe and militarily insignificant duties, including the rounding up deserters and escaped slaves. Mississippi had completely lost enthusiasm for the war, and much of the southeast of the state was controlled by deserters. Eventually, JR surrendered to the Union after Appomattox, in May 1865.

After the war and the general pardon, JR, already well practiced at keeping hs head down, was inconspicuous during the years of Reconstruction. His personal estate had dropped to $1000 by 1870; and he, his wife, and the five children remaining at home moved out to Gallmann. He was Worshipful Master of the local Masonic lodge, held a number of county sinecures, and was a low-ranking official in the Democratic Conservative Party. One might speculate he was also involved in some more lawless and secretive organizations, but the KKK and the Knights of the White Camellia did not keep a list of members.

JR died sometime in late 1882, and therefore missed by a year the white-supremacist take-over of Copiah in 1883, a result he doubtless longed for with all his heart. He had staked his fortune on slavery, and was nearly ruined after it was overthrown. But his son, William Madison Fortenberry, as we shall see, took up where he left off.

Comments

Post a Comment